This week on Film at 11 Matthew of KBOO’s Gremlin Time reviews the new film The Gray Man, and Jeff Godsil revives Roshomon, then Matthew considers the career of Fernando de Fuentes, via his film, The Phantom of the Convent, and in the book corner we look at new monographs on the British films Brief Encounter and Victim.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Film at 11, Brief Encounter, Victim

In Billy Wilder’s The Apartment, a lowly insurance drone lends out his modest living space to executives for sexual rendezvous in order to curry advancement. Wilder and I. A. L. Diamond hatched the premise from two sources. One was the producer Jennings Lang, who borrowed the lodgings of an underling to prosecute an affair with a competitor’s wife (he was later shot for his troubles). The second was Brief Encounter, the David Lean and Noel Coward drama from 1945 in which a happily married woman has a flirtation with a doctor over the course of seven Thursdays. At one point, the doctor wants to use the flat of a colleague to consummate the burgeoning affair. Wilder asked his writing partner, So what is the guy who owns the apartment supposed to do?

Admittedly this is a minor element of Brief Encounter’s legacy. The Apartment is male oriented, really, and highly critical of the amoral Mad Men world of its time. Lean and Coward’s work is woman oriented. It is narrated by the housewife, and the seven week “affair,” if you can call it that, is told in a movie-length flashback as she sits in her library watching her husband doing a crossword puzzle, wrestling with her feelings and questioning her behavior.

In his recent BFI monograph, Richard Dyer covers the film as a source of gay interest, as a film by men but giving the central woman a voice, even as she defers to men in the the patriarchal imperative in social interactions. Like Dyer, the viewer may come not to like the doctor too much. He also discusses Brief Encounter as an English – not British – movie of naturalism, realism, and craft, and defends it as a melodrama, and from that over-correcting phase in the ‘60s parallel to the rise of the kitchen sink style, that found Brief Encounter’s old fashioned-ness ridiculed by modern film magazines. He concludes, “Brief Encounter’s Englishness is something very specific and limited, but if I try to put my finger on why the film affects me so, it is this Englishness that seems to get it best. The appeal for me has something to do with nostalgia for a way of life that my family aspired to yet never quite inhabited. It has, though, mainly to do with the way the film handles emotions, the heartbreakingly touching awkwardness of its characters, what Laura describes as the English being so ‘shy and difficult’. In fact, this quality may be found in such nationally diverse films as Tokyo Story (1953), The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and Babette’s Feast (1987), but then perhaps it is very ‘English’ of me to love those films too.

It is common to characterise this way with emotions as inhibited or even emotionless. The English are cold fish with stiff upper lips. Yet this is to mistake restraint for repression and lack of expression for lack of feeling. To see Brief Encounter as only cups of tea, banal conversation and guilt is not really to see or hear it at all …

Part of the pleasure of Brief Encounter is simply the recognition of the way that restraint, not wanting to hurt, wanting to be nice, desiring comfort stymie emotional abandon. The very familiarity of this for some people is a pleasure, because it confirms part of how we experience our affective lives. There is an extra pull for me too in what I think of as a nostalgia for ordinariness: unlike some gay men, I have never wanted to be marginal and outcast, but have no option. In this perspective, the very dowdiness of Brief Encounter evokes the cosy lure of normality.

Yet if Brief Encounter recognises the difficulty of going with one’s feelings for a certain strain of Englishness, it also recognises the strain, fully registers the surging of emotion. It is because of both the social pressures toward and the genuine appeal of comfy conformity, both so meticulously realised, that the desire to love against the grain comes across so powerfully. Moreover, Brief Encounter’s recourse to music and to filmic devices also suggests, in this quite extraordinarily verbal film, the limitations of everyday speech to express emotion. Far from lacking emotion, the film is throbbing with it but also registering that emotion cannot be pinned down, summed up, that emotion is overwhelming. That is why Brief Encounter is not only a ‘lovely’, but also a vibrantly ‘good’ film.”

Molly Haskell didn’t write this in her book From Reverence to Rape it, but might have included Brief Encounter in her itinerary of films by gays otherwise coded as heterosexual. These would be films based on works by Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote, and she was echoing Pauline Kael and Mary McCarthy and probably John Simon in “finding” that these films disguised their real concern with homosexual manners within a more commercial tale of sophisticated, or not, heterosexuals. Coward happened to be gay, but there is no evidence that the film, and the short play on which it was based, was anything other than what it seems, a poignant tale of love frustrated by the rigidity of society’s mores.

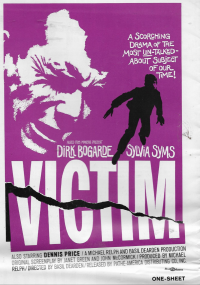

Victim, on the other hand, explicitly deals with the secret life of gay men in the early 1960s when homosexuality was literally illegal.

Made some 15 years later, Victim yet tackles a similar marital situation, a married partner who is tempted to stray, but in this case, Dirk Bogarde is gay, has renounced his urges to honor his wife who knows of them, and also to protect his career as a barrister, but then is threatened with blackmail by an unscrupulous pair of criminals. This is a social protest story with elements of a police procedural, as Bogarde’s character tracks down the blackmail ring after the suicide of a young man he cared about. Also like Brief Encounter, the film comes with a heavy, lush piano score, here sometimes at odds with its realism.

The remit of John Coldstream in his BFI monograph on Victim is to explore the notion that a film can change society. In this case, a film did, as the work spurred on efforts to decriminalize homosexuality in England shortly thereafter. To this end, the author devotes a lot of time to just how the film was made, how the filmmakers navigated the then-strong censorship review board before production began, and how Bogarde developed his character. The actor is often praised for his bravery for taking on the part at the time, as he had been a teen idol in the ‘50s while masking his real sexual identity, and this is true, but it is also true of a secondary character played by Dennis Price, another long time stage and screen performer.

Mr. Coldstream concludes with a fine tribute to Victim’s value. “Thanks, in no small measure to the reaction on Victim’s release, public opinion shifted in line with artistic expression; but it took seven more years for understanding, if not compassion, to be translated into legislation. Leo Abse, the colorful labor MP for, Pontypool, would be thwarted twice – in 1962 and 1965 – in his attempts to persuade the House of Commons that the main Wolfenden recommendations should be implemented. The Lords proved more amenable, voting in 1965 for reform as championed by the Earl of Arran; but there was further frustration in the Commons the following year, when a general election arrested progress. Abse persisted, until finally he, too, prevailed. On 27th July 1967, the Sexual Offenses Bill received the Royal Assent. Introducing the third reading as a pass through the Lords, Arran said: “Because of the Bill, perhaps 1 million human beings will be able to live in greater peace." Soon afterwards he would repeat this prescient remark, the tense, modified to the present, when he wrote to Dirk Bogarde acknowledging the part the film had made in forcing change. He meant it, too. Interviewed by Gay News, in 1976, he said: “It had a significant impact on the public, when it was first shown." His efforts to secure reform had been made that much easier.

Basil Dearden's son, James, the director and screenwriter, who was 11 when Victim opened, is in no doubt that it "contributed to the debate, and had a real influence over the eventual liberalization of the law, and the change in public attitudes.” To this day, he meets men "who grab my hand and say how thankful they were to the film, how it was literally a revelation to be sitting in some cinema in some provincial town, and realize that there were other people who felt like them. It's not often that a film changes peoples lives, but I believe that Victim is one of them"

His father’s modest little thriller may never be rated in the cognoscenti’s top tens: indeed, when in February 2011, Time Out published a list of the "100 best British films" Victim was nowhere to be found. Unlike all the usual suspects, however, it turned out to be a Mighty Mouse, punching way above its weight. A movie that truly mattered.”

- KBOO